The impact of digitalisation on West African cities

The example of mobile money

Digitalisation is changing the world at a rapid pace, as we see on a daily basis, and Africa is at the forefront. It represents an opportunity both in terms of business and social development. This digital revolution offers unique opportunities in the design and management of urban spaces.

From Dakar to Djibouti, from Cape Town to Tunis, cities and their populations are integrating these innovations as best they can. And regardless of whether they work or not, they are having a lasting and transformative impact on the continent.

The 2021 report entitled “The use of digital technology in the context of West African cities” (Centre of Excellence in Africa (EXAF), EPFL), clearly demonstrates that the use of digital technology in the African context offers opportunities to make cities “smarter” and the lives of its people more comfortable.

© Fiona Graham / WorldRemit

© Fiona Graham / WorldRemit

However, while digitalisation heralds profound changes in society, such as mobile money, another – more traditional – revolution is under way: demography.

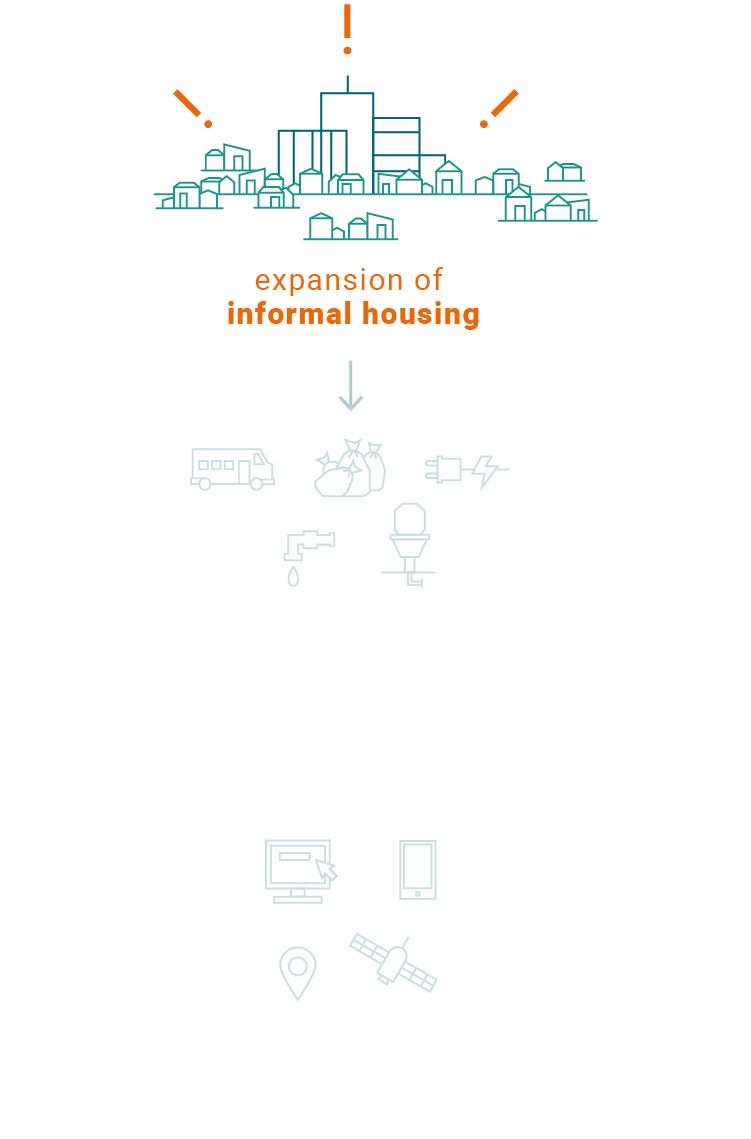

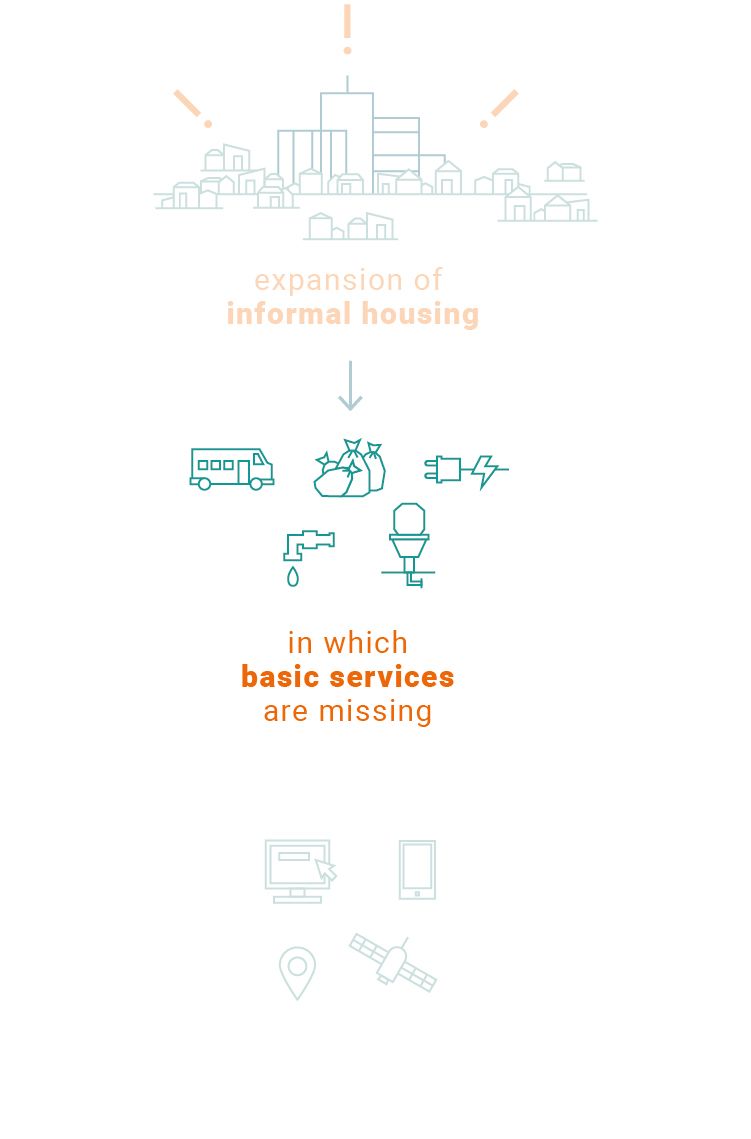

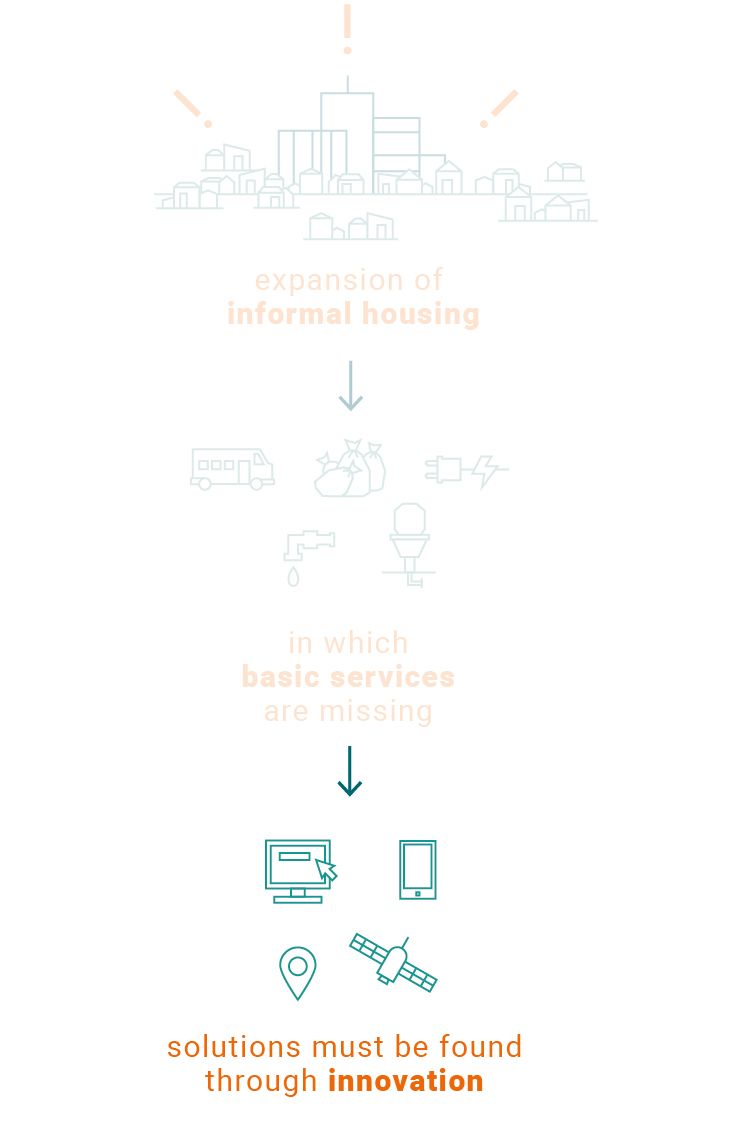

Just imagine the doubling of the land surface in today’s large cities and you will have an idea of the challenges that states and local authorities will be facing in coming decades. While urban areas are characterised by a higher overall income than the rest of the country, in most sub-Saharan African countries, rapid urban growth is not always linked to economic development. Instead, it is often the result of the expansion of informal and precarious housing, which shelters the majority of vulnerable city dwellers (World Bank, 2017) and where access to basic urban services is limited.

In such cases, cities often fail to reap the benefits usually associated with urban growth, because poor residents remain caught in a poverty trap.

Public and private sector actors must address the challenges of the vulnerable urban citizens in order to enable African cities to become real engines of economic growth. Urban authorities must find innovative ways to make basic services, such as access to water and electricity, waste management, sanitation and transport, more accessible to citizens in need (World Bank, 2018).

Cities as testing grounds for innovative solutions

It is increasingly clear that the use of digital technologies to solve urban problems is still mostly untapped potential. The spread of new technologies and mobile connectivity has recently enabled the proliferation of digital solutions that appear to make vital basic services more efficient, accessible and affordable (OECD, 2020). For example, the spread of mobile money has been a key catalyst for financial inclusion across sub-Saharan Africa and has enabled the development of solutions tailored to the realities of the poor.

Infrastructure

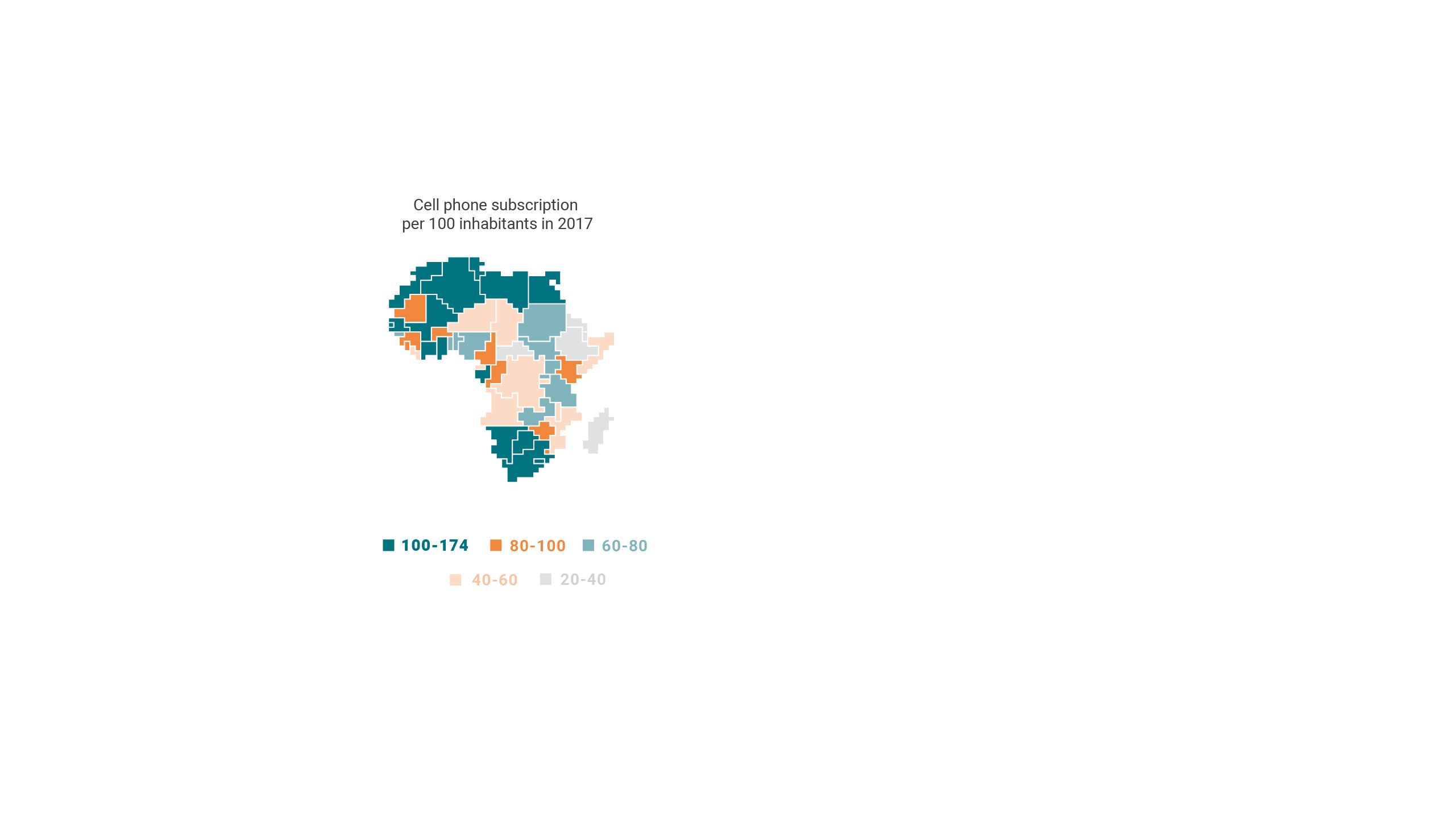

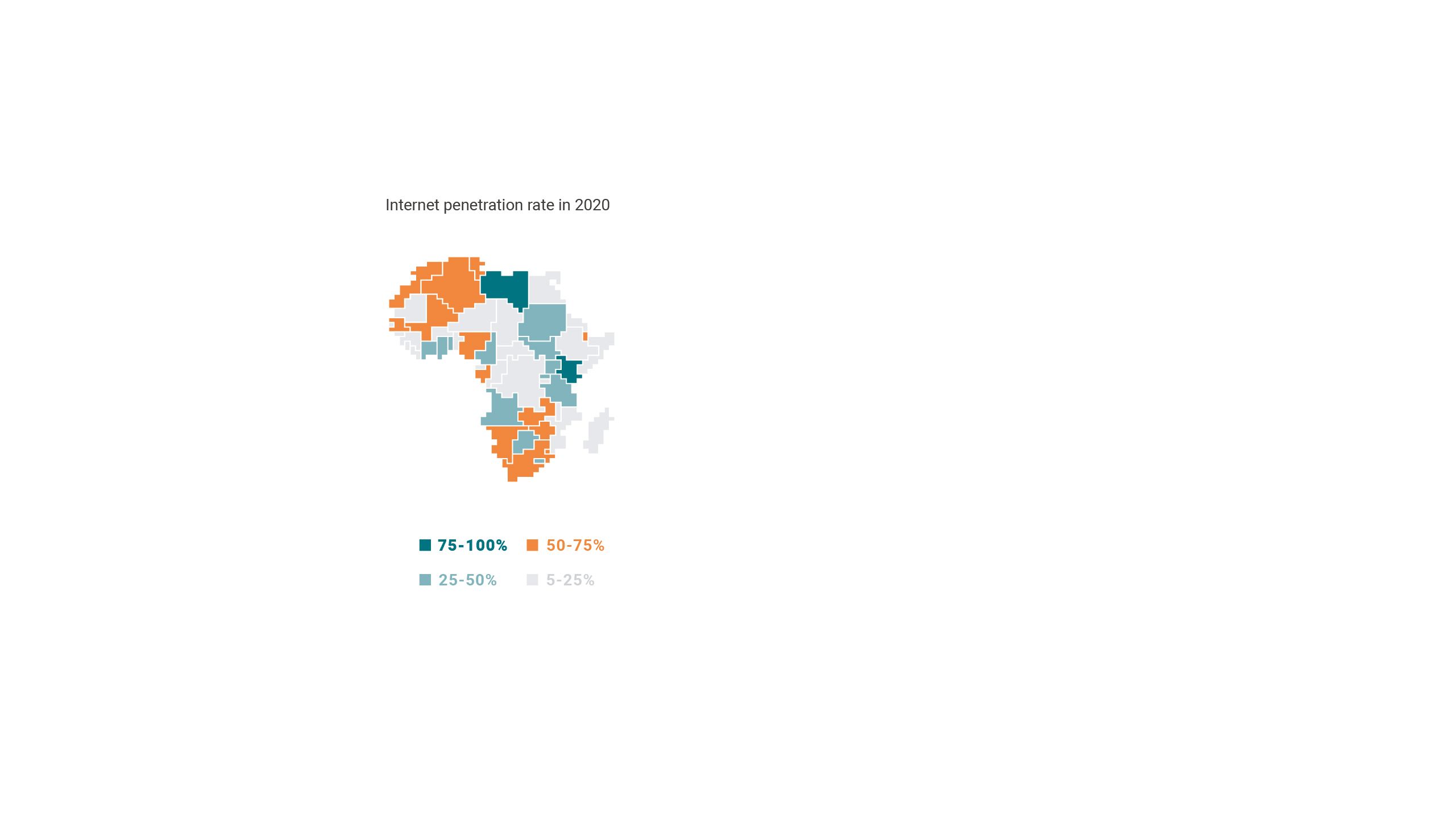

In just a few years, the proliferation of mobile phone networks has transformed communications in sub-Saharan Africa. It has also allowed Africans to skip the development of the landline telephone and move directly into the digital age.

Governments are increasingly prioritising Internet-driven growth, as in Benin, Togo and Côte d’Ivoire (CIO Mag, 2021). They all have ambitious plans to extend high-speed Internet access to their entire populations. Most countries have developed national digital strategies, but many are still in the early stages of implementation.

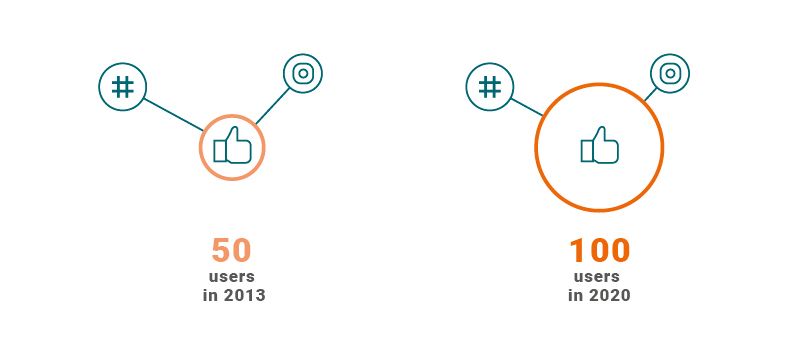

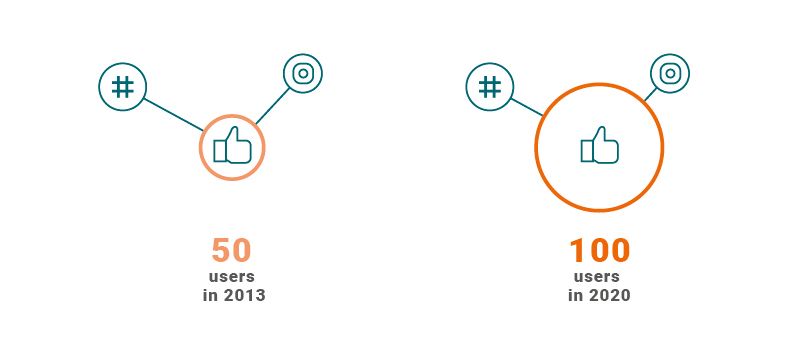

Over the next decade, the number of digital - and therefore Internet - users in Africa is expected to increase to 16% of the global total. The sharp increase in the number of phones connected to the Internet explains the surge of accounts in social networks in sub-Saharan Africa, which have risen from 50 to 100 million since 2013. At the same time, the number of mobile phone subscriptions has risen from 581 million to 882 million in 2020, as shown by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU). It is interesting to note that the penetration rate of mobile telephony is particularly high across the continent, especially in West and Southern Africa where the number of mobile subscriptions exceeds 100% of the population. Beyond its economic impact, the digital transition should enable African governments to improve the standard of living of their citizens, especially the poorest.

© KC Nwakalor for USAID / Digital Development Communications

© KC Nwakalor for USAID / Digital Development Communications

In addition to being a means of communication, the mobile phone is widely used in sub-Saharan Africa to make or receive payments (mobile money) and plays an important role, for example, in accessing political information, joining social networks, obtaining health and medical information, and in searching of/or applying for a job.

Governments are increasingly prioritising Internet-driven growth, as in Benin, Togo and Côte d’Ivoire (CIO Mag, 2021). They all have ambitious plans to extend high-speed Internet access to their entire populations. Most countries have developed national digital strategies, but many are still in the early stages of implementation.

Over the next decade, the number of digital - and therefore Internet - users in Africa is expected to increase to 16% of the global total. The sharp increase in the number of phones connected to the Internet explains the surge of accounts in social networks in sub-Saharan Africa, which have risen from 50 to 100 million since 2013. At the same time, the number of mobile phone subscriptions has risen from 581 million to 882 million in 2020, as shown by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU). It is interesting to note that the penetration rate of mobile telephony is particularly high across the continent, especially in West and Southern Africa where the number of mobile subscriptions exceeds 100% of the population. Beyond its economic impact, the digital transition should enable African governments to improve the standard of living of their citizens, especially the poorest.

In addition to being a means of communication, the mobile phone is widely used in sub-Saharan Africa to make or receive payments (mobile money) and plays an important role, for example, in accessing political information, joining social networks, obtaining health and medical information, and in searching of/or applying for a job.

© KC Nwakalor for USAID / Digital Development Communications

© KC Nwakalor for USAID / Digital Development Communications

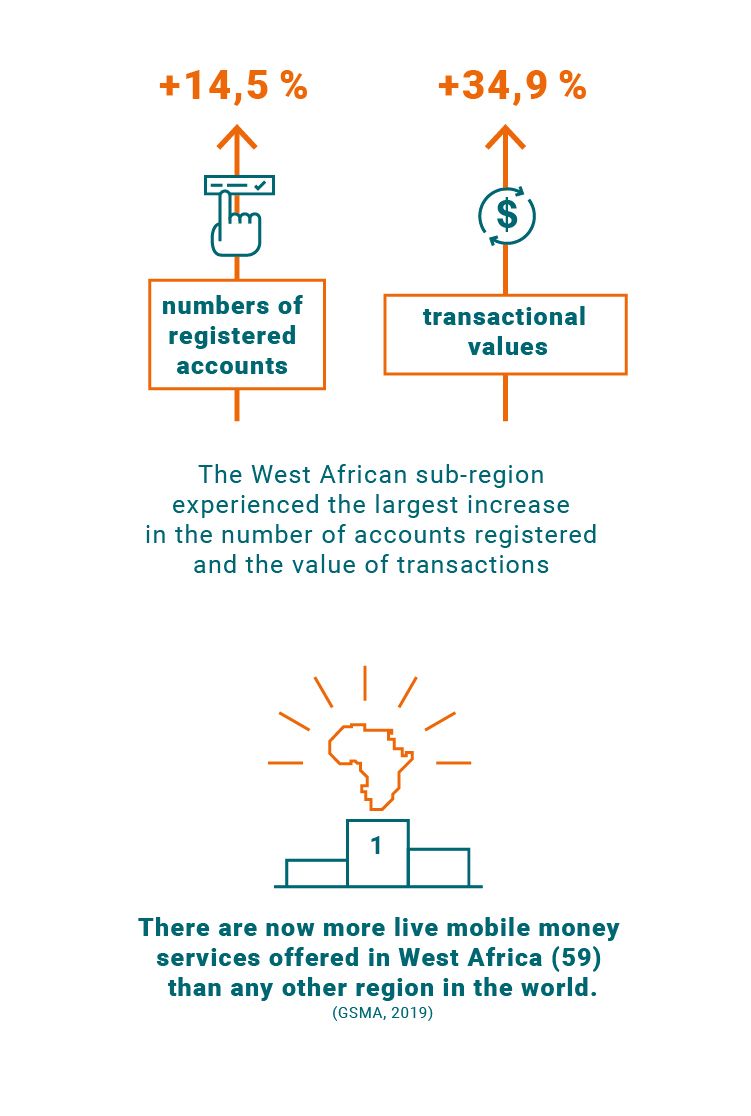

Sub-Saharan Africa has been at the forefront of the mobile money sector for more than a decade and in 2020 it continued to account for the majority of its growth.

At the end of the year, there were 548 million registered accounts in the region, of which over 150 million were active on a monthly basis.

The number of mobile money accounts now exceeds that of traditional deposit accounts.

21% of adults in sub-Saharan Africa have a mobile money account.

However, this penetration is uneven, since the strongest presence is concentrated in East Africa, particularly in Kenya. Gabon, Namibia and Zimbabwe are also experiencing strong growth.

The highest growth rates for this technology are in West Africa, notably in Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Senegal, where more than 30% of adults now have a mobile money account.

Importantly, 200,000 Kenyan households have been lifted out of extreme poverty as a result of adopting a mobile money account.

Women are still less likely than men to have a mobile money account, even though mobile money has the potential to increase inclusion and close the gender gap in access to financial services.

Mobile money

The mobile money financial services sector is booming in West Africa. It has even become a pioneer of mobile money in Africa.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, digital payments were increasingly used to reduce the risks associated with the exchange of cash. This is the case in Senegal, for example, where it has become common to pay for a taxi with Orange Money. It’s the most popular mobile money service in West Africa, offered by the French telecommunications group Orange.

In the coming years, thanks to lower prices and a new generation of young “digital natives”, the GSMA (Global System for Mobile Communications Association) predicts a dramatic increase in smartphone usage in sub-Saharan Africa. By 2020, it had already reached 50% of total connections. Moreover, connecting to 3G and 4G networks via a smartphone provides the opportunity to improve access to information and other services.

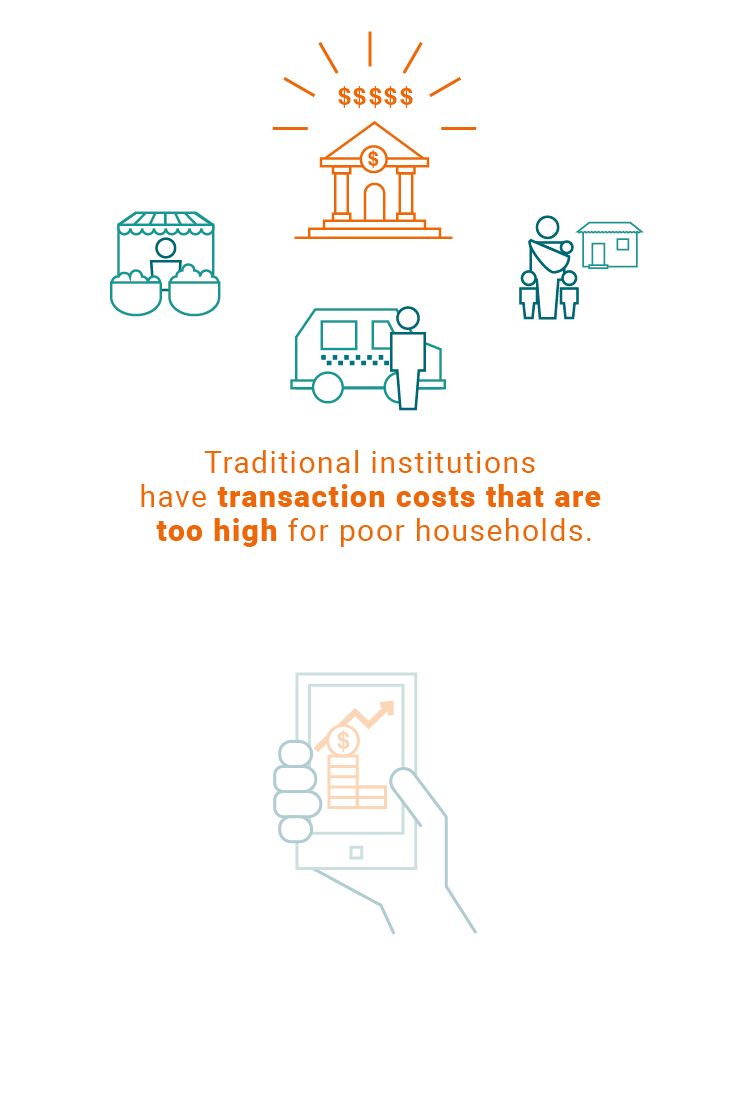

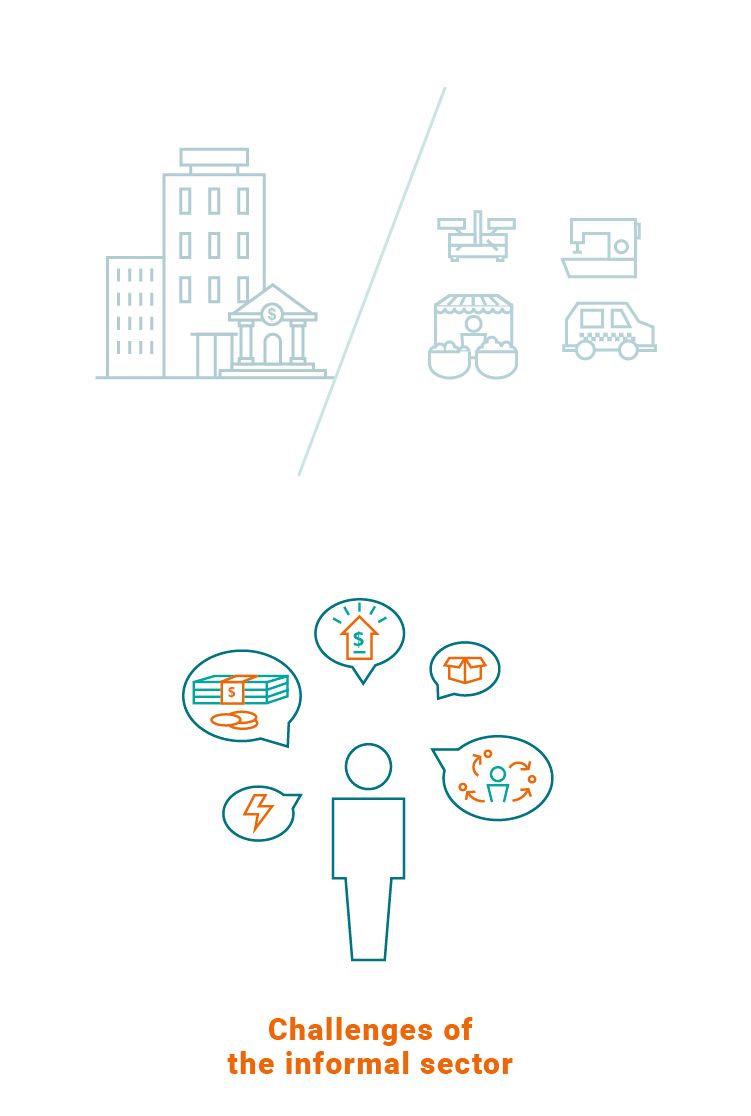

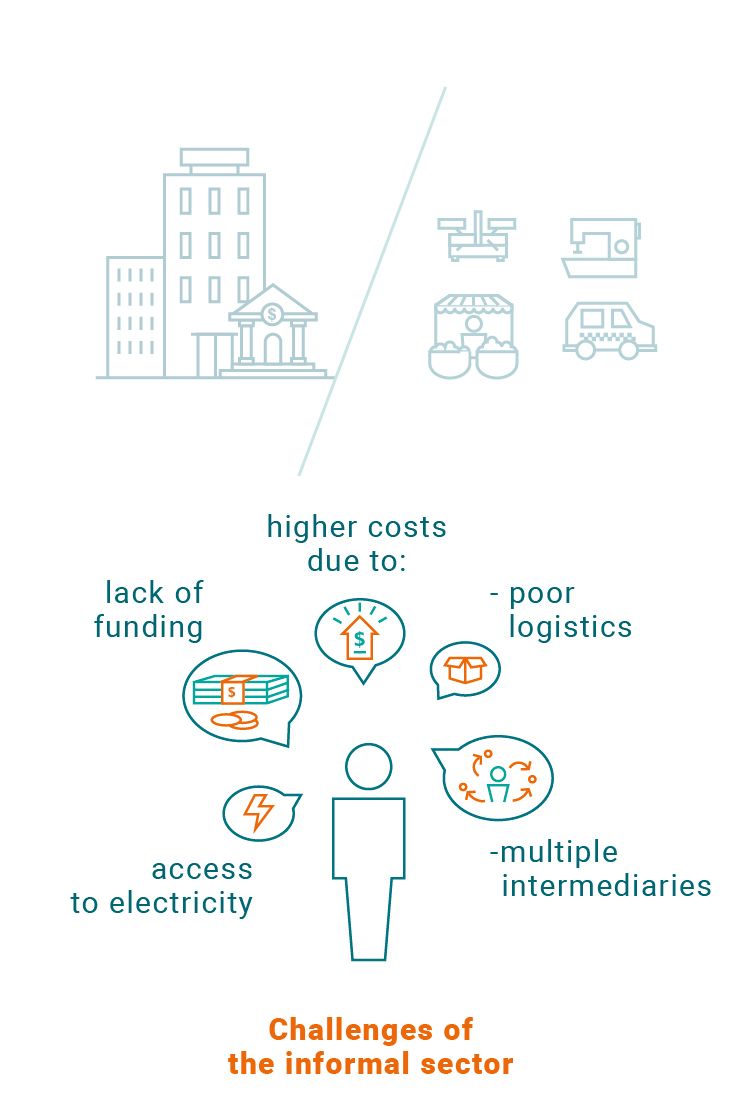

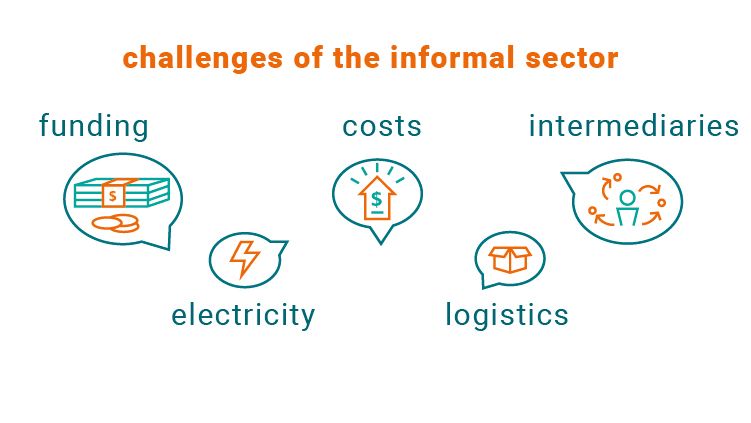

Challenges of the informal sector

Efficient financial systems are critical to poverty reduction and to increase financial inclusion. Traditional banking institutions have high transaction costs, which make it extremely difficult for the poorest households to maintain savings and deposit accounts. The experience of countries in Eastern and Southern Africa confirms that mobile money offers a unique opportunity to encourage and strengthen financial inclusion, with the potential of increasing economic growth and reducing inequality.

© Fiona Graham / WorldRemit

© Fiona Graham / WorldRemit

Businesses in Africa are largely organised into the formal and informal sectors. Formal sector enterprises are generally large companies such as banks and insurance companies, telecommunications operators, agribusinesses, and oil and mining companies. Small and medium-sized enterprises in the formal sector are quite limited in size and number, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Informal sector enterprises are generally small, consisting of less than five employees. In most African countries, the informal sector accounts for a significant share of economic activity.

Among people working in the informal sector or in low-income activities, a mobile money account is the most common way to pay or get paid for a service.

The digital economy offers opportunities to address the challenges faced by informal businesses and workers, who often have limited access to finance and little use of modern business practices, including accounting (Mahadea and Zogli, 2018). In the informal sector, access to electricity is less certain, and the general business environment is unstable. However, the vast majority of informal sector workers own a mobile phone, often used for both private and business purposes. To date, most successful companies in the African digital economy are addressing the problems faced by businesses or workers in the informal sector. The widespread use of mobile money in several African countries, such as Kenya, Côte d’Ivoire and Mali, is one example.

© John O'Bryan / USAID

© John O'Bryan / USAID

Despite its potential for increasing growth, digital technology in African cities still lacks maturity and its use is lower than in developed economies. There is a general reluctance to venture and invest in new knowledge and technologies by governments and industry in most African countries. However, the appropriate adoption and judicious use of the digital industry for the benefit of cities offers undeniable opportunities to solve certain socio-economic problems and industrial challenges.

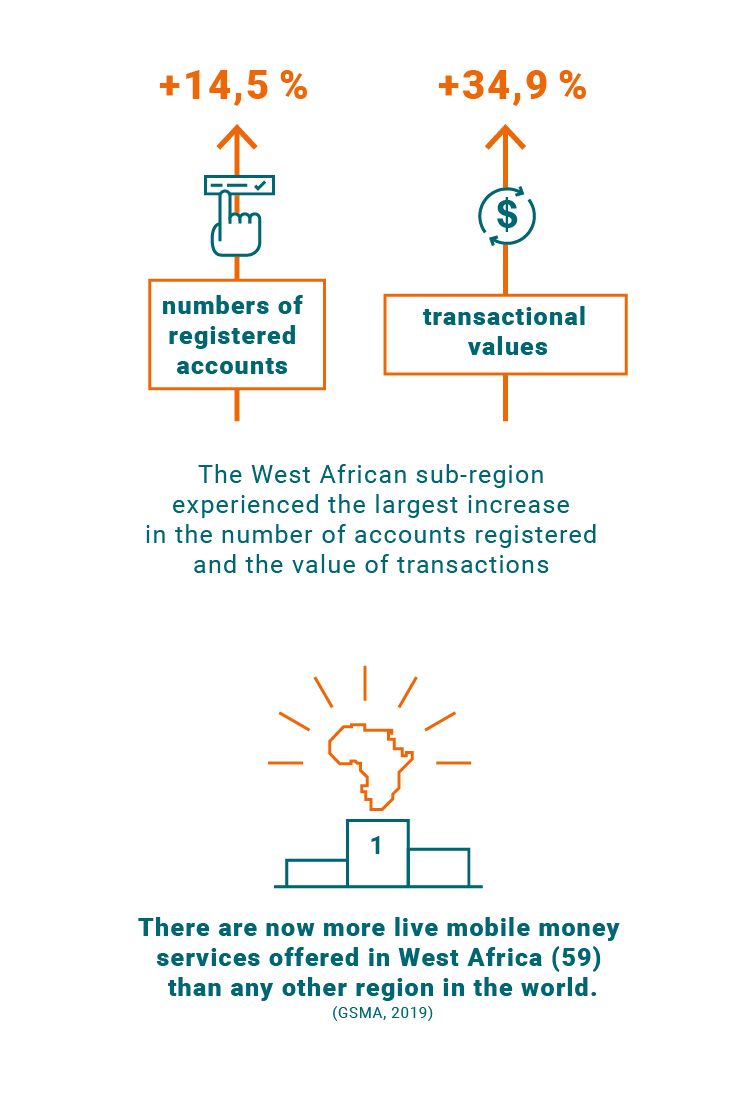

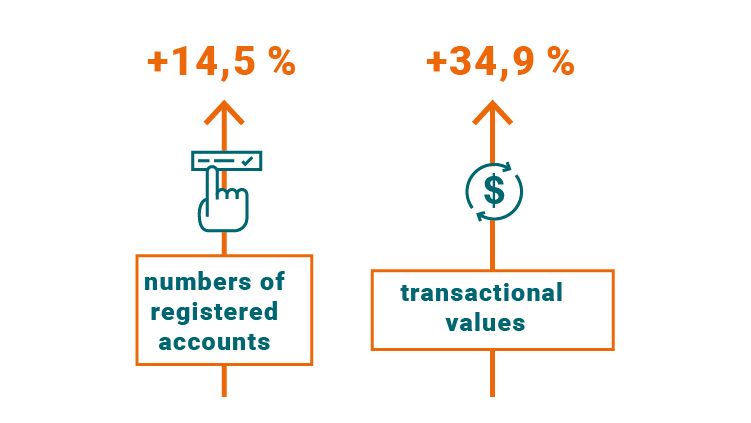

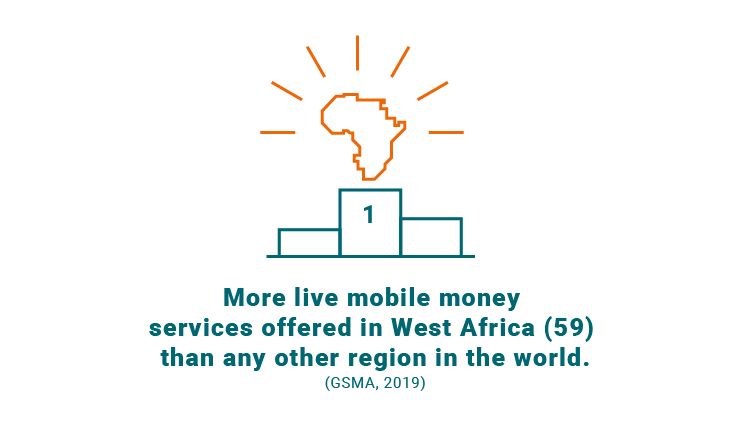

The West African sub-region experienced the largest increase in the number of accounts registered (14,5%) and the value of transactions (34,9%). There are now more live mobile money services services offered in West Africa (59) than any other region in the world.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, digital payments were increasingly used to reduce the risks associated with the exchange of cash. This is the case in Senegal, for example, where it has become common to pay for a taxi with Orange Money. It’s the most popular mobile money service in West Africa, offered by the French telecommunications group Orange.

In the coming years, thanks to lower prices and a new generation of young “digital natives”, the GSMA (Global System for Mobile Communications Association) predicts a dramatic increase in smartphone usage in sub-Saharan Africa. By 2020, it had already reached 50% of total connections. Moreover, connecting to 3G and 4G networks via a smartphone provides the opportunity to improve access to information and other services.

Challenges of the informal sector

Efficient financial systems are critical to poverty reduction and to increase financial inclusion. Traditional banking institutions have high transaction costs, which make it extremely difficult for the poorest households to maintain savings and deposit accounts. The experience of countries in Eastern and Southern Africa confirms that mobile money offers a unique opportunity to encourage and strengthen financial inclusion, with the potential of increasing economic growth and reducing inequality.

© Fiona Graham / WorldRemit

© Fiona Graham / WorldRemit

Businesses in Africa are largely organised into the formal and informal sectors. Formal sector enterprises are generally large companies such as banks and insurance companies, telecommunications operators, agribusinesses, and oil and mining companies. Small and medium-sized enterprises in the formal sector are quite limited in size and number, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Informal sector enterprises are generally small, consisting of less than five employees. In most African countries, the informal sector accounts for a significant share of economic activity.

Among people working in the informal sector or in low-income activities, a mobile money account is the most common way to pay or get paid for a service.

The digital economy offers opportunities to address the challenges faced by informal businesses and workers, who often have limited access to finance and little use of modern business practices, including accounting (Mahadea and Zogli, 2018). In the informal sector, access to electricity is less certain, and the general business environment is unstable. However, the vast majority of informal sector workers own a mobile phone, often used for both private and business purposes. To date, most successful companies in the African digital economy are addressing the problems faced by businesses or workers in the informal sector. The widespread use of mobile money in several African countries, such as Kenya, Côte d’Ivoire and Mali, is one example.

© John O'Bryan / USAID

© John O'Bryan / USAID

Despite its potential for increasing growth, digital technology in African cities still lacks maturity and its use is lower than in developed economies. There is a general reluctance to venture and invest in new knowledge and technologies by governments and industry in most African countries. However, the appropriate adoption and judicious use of the digital industry for the benefit of cities offers undeniable opportunities to solve certain socio-economic problems and industrial challenges.

Innovation

Digital innovations in the urban environment can address needs in a wide range of sectors, such as health, the environment, mobility, public administration services and education.

Complete digitisation is, therefore, presented as a way to build a sustainable society.

Despite technical and institutional constraints on the growth of the digital economy in Africa, technology and innovation hubs have emerged.

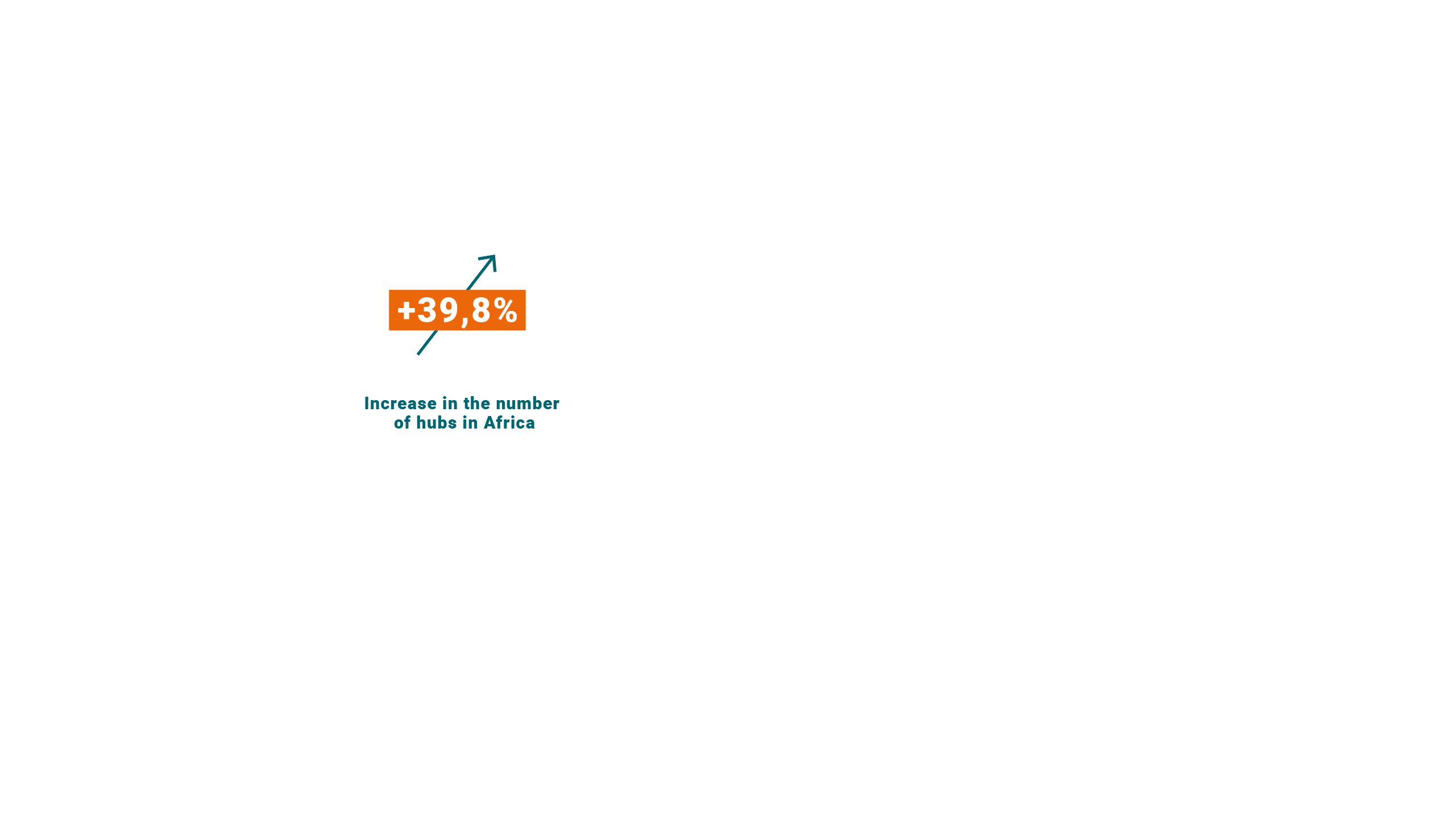

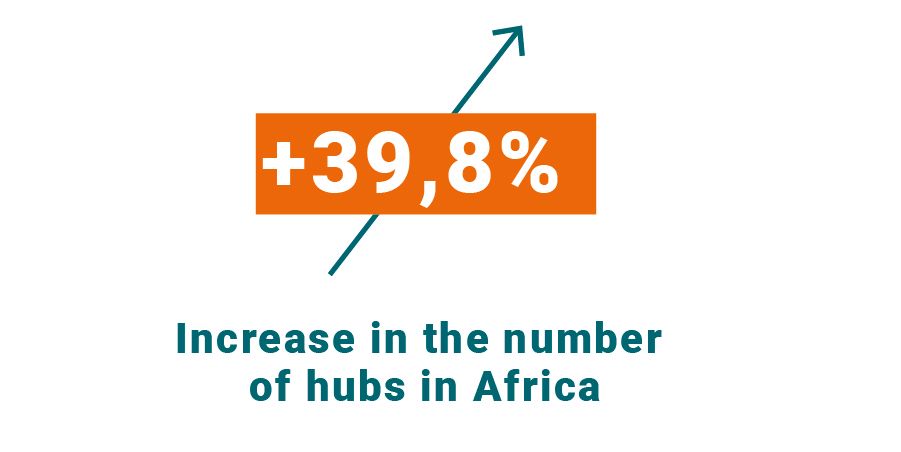

Hubs have the capacity to solve economic, social and ecological problems through digital entrepreneurship tools and business innovations (Jiménez, 2018). The number of these structures in Africa has increased from 442 in 2018 to 618 in 2019 (including 22 in Côte d’Ivoire and 14 in Mali), an increase of 39.8% (Giuliani and Ajadi, 2020).

This opens up new opportunities for the continent, as digital technologies are no longer just imported: innovation spaces establish favourable development environments to create local and specific solutions.

Afrilabs

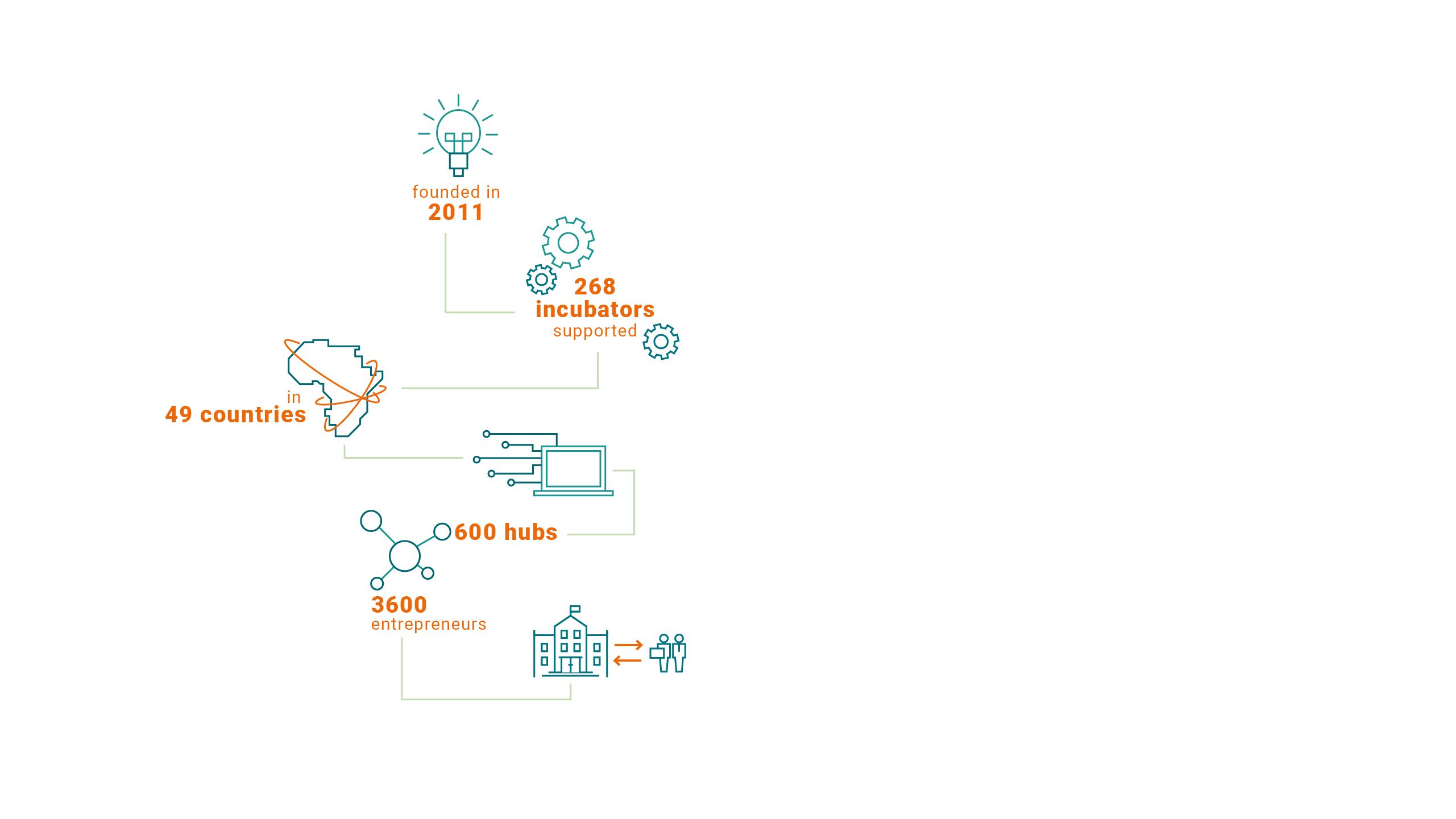

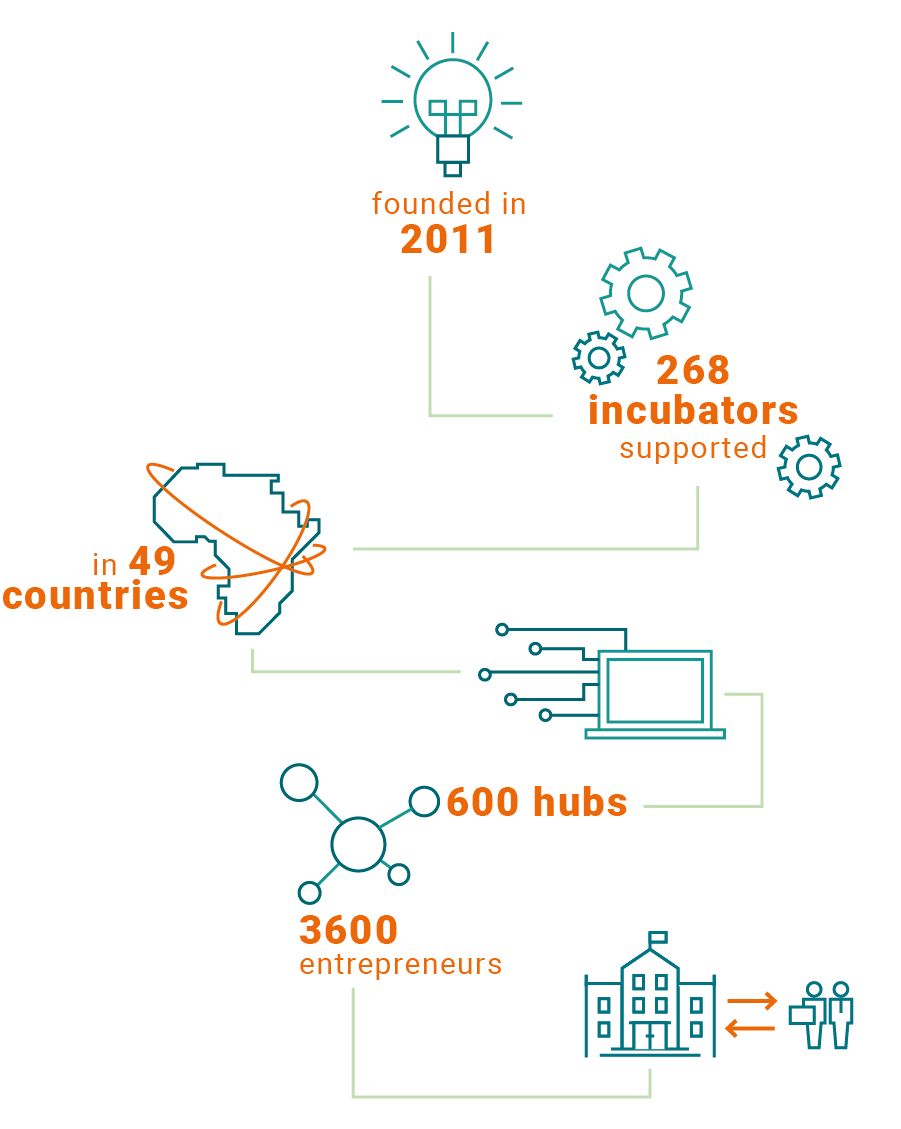

For example, AfriLabs, founded in 2011 by Rebecca Enonchong, supports a network of 268 incubators in 49 African countries and is positioned as one of the matrices of digital innovation in Africa. It aims to accelerate innovations that drive economic growth and job creation through innovative digital governance, including local universities.

Thus, AfriLabs enters the spheres of development and action research with African universities. For the French Development Agency (AFD), AfriLabs is a key intermediary to reach 600 hub managers, 3,600 entrepreneurs and developers, but above all 200,000 stakeholders in the African technology and innovation ecosystem in West Africa.

Yabacon Valley

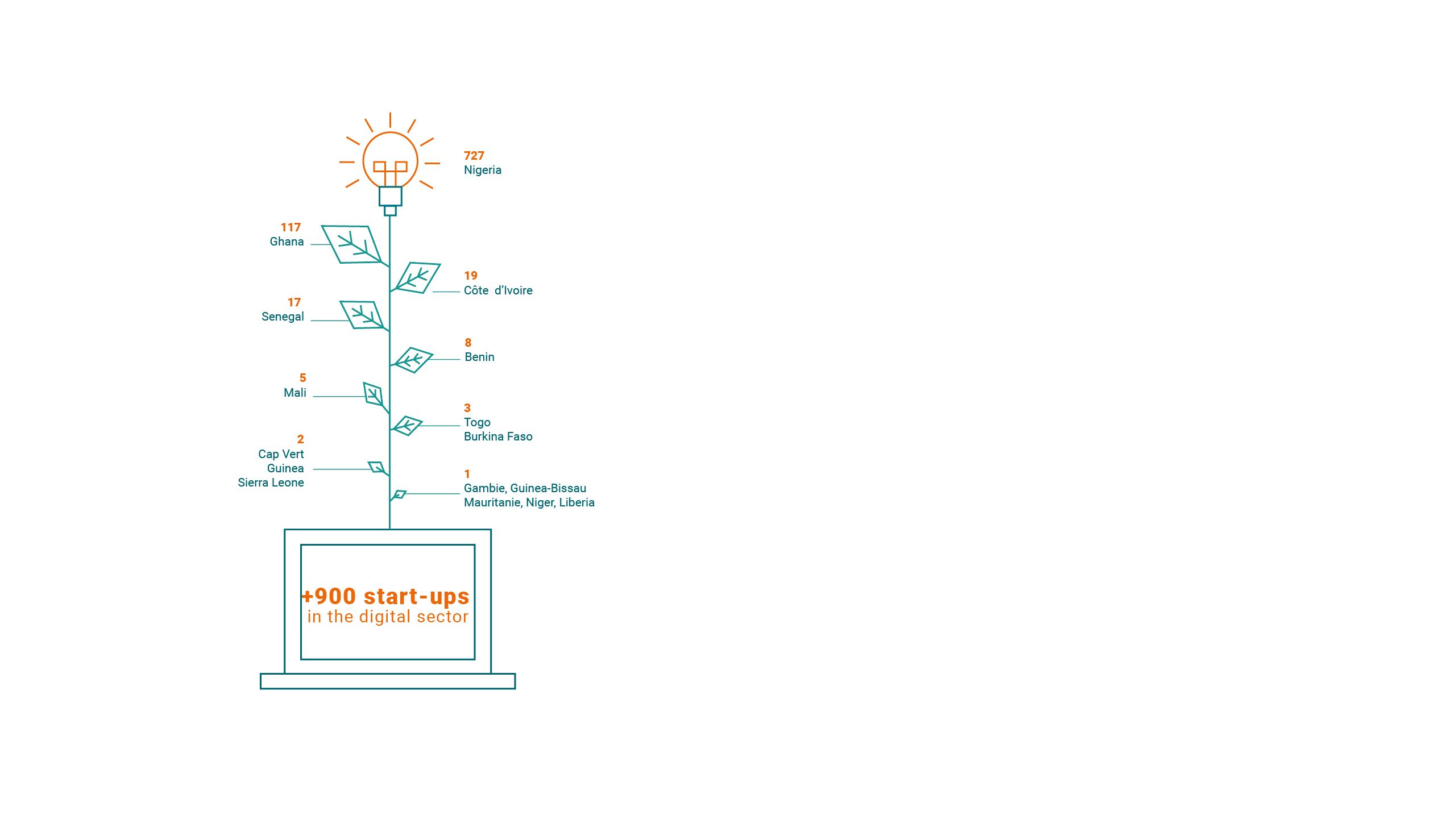

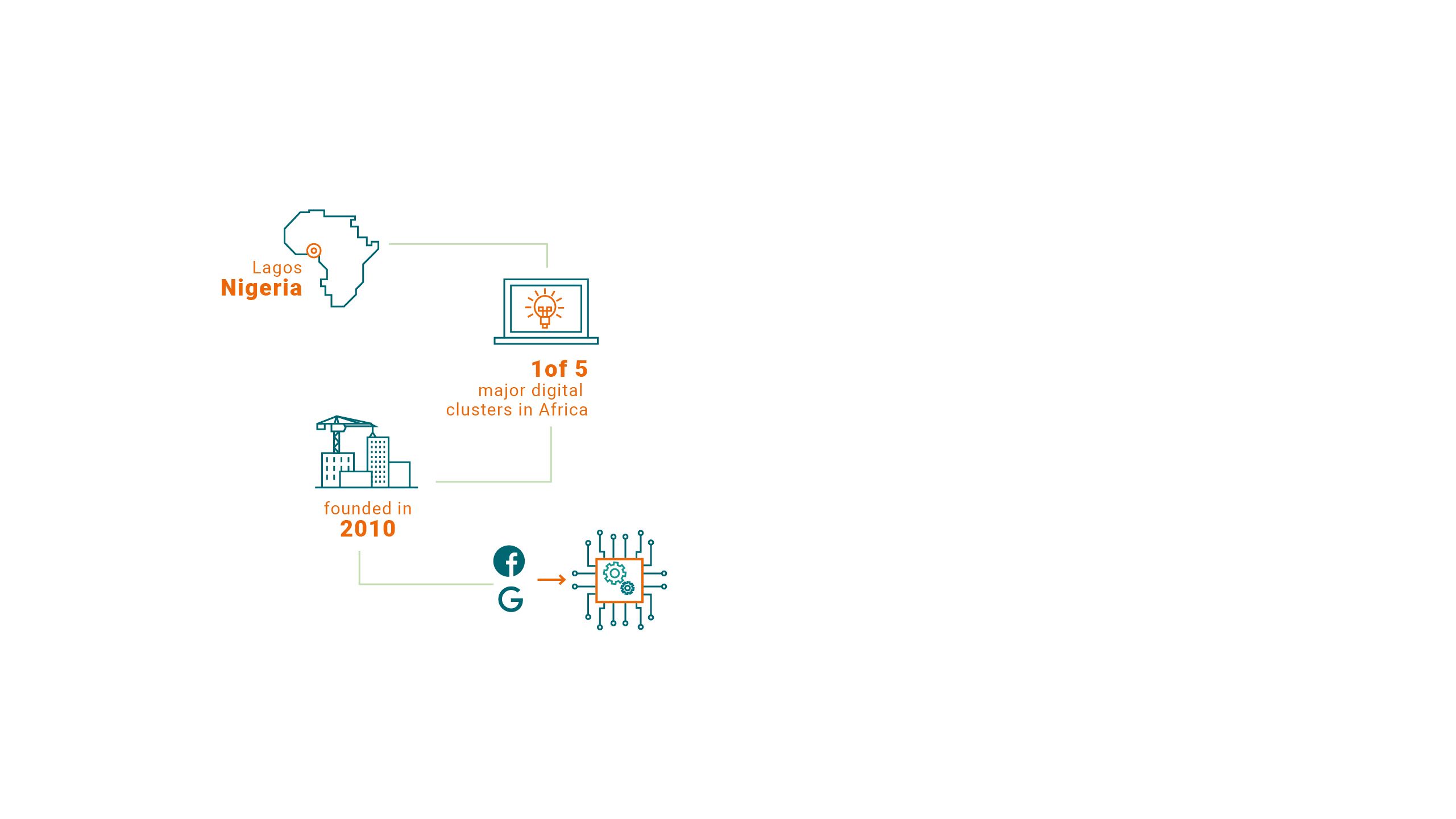

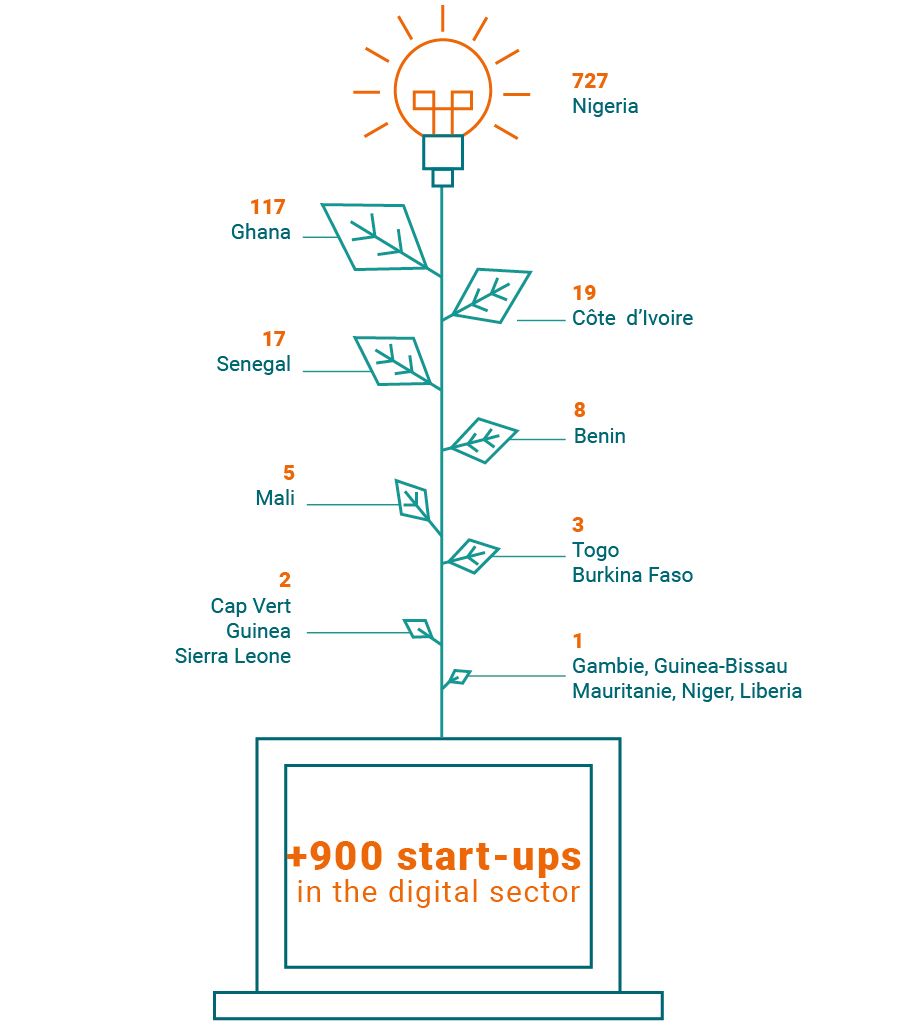

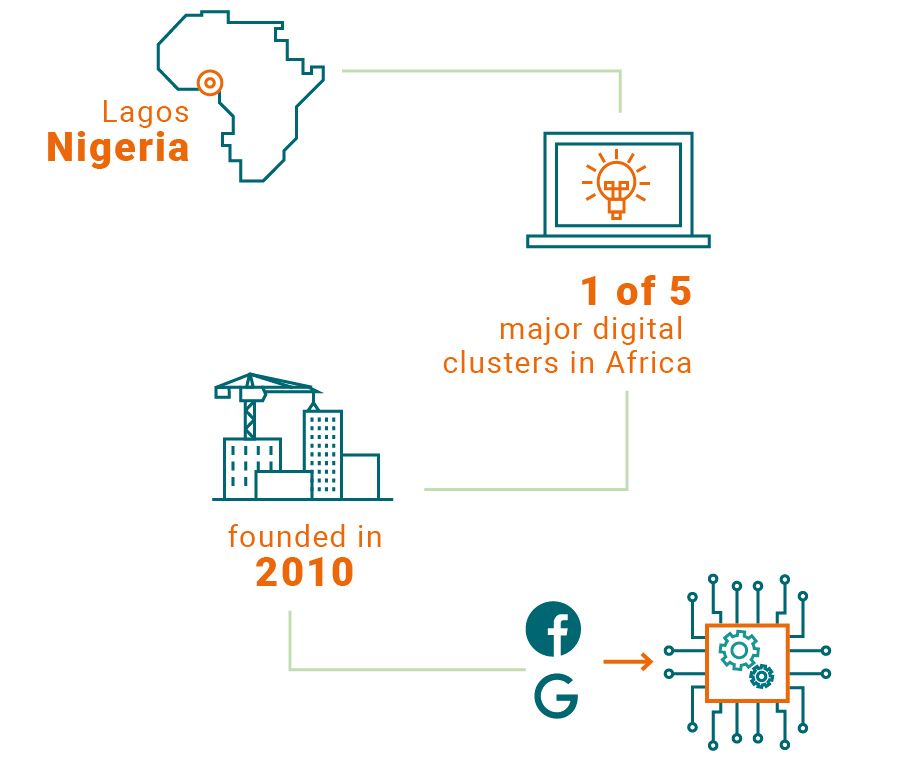

In West Africa, there are over 900 digital start-ups (StartupRanking, 2021), making this region the most entrepreneurially dynamic in sub-Saharan Africa. However, West African countries show significant disparities in the development of these digital ecosystems. For example, Nigeria is distinguished by the existence of the Yabacon Valley, which is classified as one of the five major digital hubs in Africa.

Created in 2010, to allow economic agents to bypass the traffic congestion in the centre of Lagos and to offer development opportunities to this new digital industry, the Yabacon Valley first hosted the major figures of telecommunications in Africa, then CCHub, one of the most important hubs in Africa. In the second half of the last decade, Marc Zuckerberg’s arrival in Yabacon Valley was followed by the installation of a start-up incubator Facebook’s NG_Hub and by Google’s Launchpad Space in Lagos.

© Stephen Olatunde

© Stephen Olatunde

The investment of the GAFAMs (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon et Microsoft) in the emergence of local skills in the digital sector has led to an explosion in the number of start-ups in Nigeria. It has positioned the Yabacon Valley as a privileged investment site.

Côte d'Ivoire

In the rest of the region, while the digital ecosystems are less developed and more fragile, policy efforts and investments in telecommunications still provide the backbone for a dynamic digital sector development.

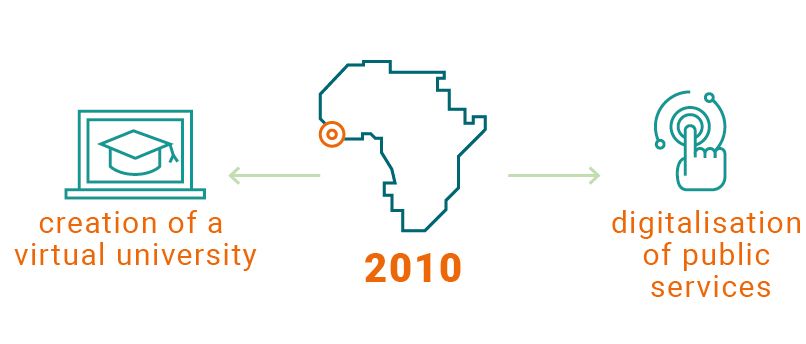

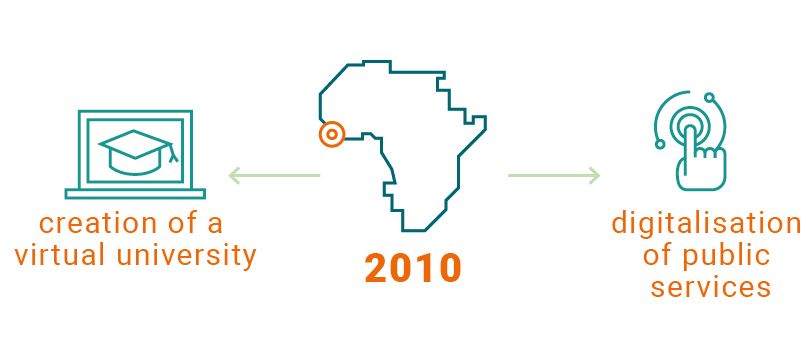

In the second half of the last decade, Côte d’Ivoire showed significant political commitment to this issue by supporting the digitisation of part of its public services. The advent of a digital university for 3,500 students, is a symbol of the place that digital technology is taking in constructing the near future.

Abidjan continues its race to become the leading innovative ecosystem in French-speaking West Africa, with more than 20 innovation hubs. It includes Seedspace, a connected coworking hub present in emerging countries, as well as four Jokkolabs - coworking and support spaces for digital projects imported from Dakar.

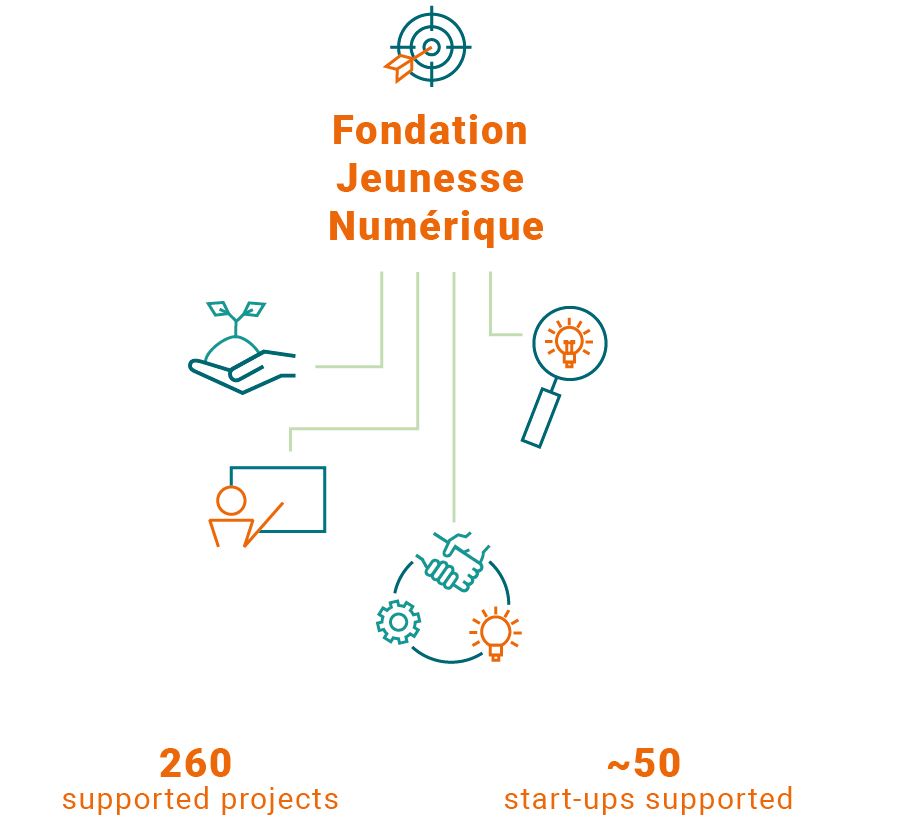

The results are already observable in terms of the trickle-down of technology into Ivorian society. The Fondation Jeunesse Numérique, headed by telecommunications engineer Linda Nanan Vallée, plays an important role as an incubator of digital innovations in Côte d’Ivoire. It has enabled the incubation of more than 260 digital projects and supported some fifty start-ups.

One of these start-ups, Moja Ride, offers a cashless booking and payment system for all collective taxis (“Woro-Woro”) and minibuses (“Gbaka”) in the Abidjan area.

The success of the initiative, which allows the driver to understand the transport needs, save time and have better transparency in the management of the money collected, has supported its development and integration into daily life. A year after its launch, in 2020, Moja Ride started operating in partnership with O-CITY, owned by the US investment bank BPC, in 130 cities around the world, to develop its payment platform.

Senegal

In Senegal, since 2017, the operator Orange has set up Orange Digital Ventures Africa (ODVA), a €50 million investment fund dedicated to economic and social innovation projects based on mobile applications. The Government has launched a 25-hectare Digital Technology Park (PTN) project in Diamniadio, on the outskirts of Dakar. A cornerstone of the national digital economy strategy “Senegal Digital 2025”, the technopole aims to support a genuine digital research economy in order to sustain the West African digital ecosystem. The Park will offer hosted companies a whole connected environment, including a data centre, an audiovisual production studio, as well as training and research institutions.

Complete digitisation is, therefore, presented as a way to build a sustainable society.

Despite technical and institutional constraints on the growth of the digital economy in Africa, technology and innovation hubs have emerged.

Hubs have the capacity to solve economic, social and ecological problems through digital entrepreneurship tools and business innovations (Jiménez, 2018). The number of these structures in Africa has increased from 442 in 2018 to 618 in 2019 (including 22 in Côte d’Ivoire and 14 in Mali), an increase of 39.8% (Giuliani and Ajadi, 2020).

This opens up new opportunities for the continent, as digital technologies are no longer just imported: innovation spaces establish favourable development environments to create local and specific solutions.

Afrilabs

For example, AfriLabs, founded in 2011 by Rebecca Enonchong, supports a network of 268 incubators in 49 African countries and is positioned as one of the matrices of digital innovation in Africa. It aims to accelerate innovations that drive economic growth and job creation through innovative digital governance, including local universities.

Thus, AfriLabs enters the spheres of development and action research with African universities. For the French Development Agency (AFD), AfriLabs is a key intermediary to reach 600 hub managers, 3,600 entrepreneurs and developers, but above all 200,000 stakeholders in the African technology and innovation ecosystem in West Africa.

Yabacon Valley

In West Africa, there are over 900 digital start-ups (StartupRanking, 2021), making this region the most entrepreneurially dynamic in sub-Saharan Africa. However, West African countries show significant disparities in the development of these digital ecosystems. For example, Nigeria is distinguished by the existence of the Yabacon Valley, which is classified as one of the five major digital hubs in Africa.

Created in 2010, to allow economic agents to bypass the traffic congestion in the centre of Lagos and to offer development opportunities to this new digital industry, the Yabacon Valley first hosted the major figures of telecommunications in Africa, then CCHub, one of the most important hubs in Africa. In the second half of the last decade, Marc Zuckerberg’s arrival in Yabacon Valley was followed by the installation of a start-up incubator Facebook’s NG_Hub and by Google’s Launchpad Space in Lagos.

© Stephen Olatunde

© Stephen Olatunde

The investment of the GAFAMs (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon et Microsoft) in the emergence of local skills in the digital sector has led to an explosion in the number of start-ups in Nigeria. It has positioned the Yabacon Valley as a privileged investment site.

Côte d'Ivoire

In the rest of the region, while the digital ecosystems are less developed and more fragile, policy efforts and investments in telecommunications still provide the backbone for a dynamic digital sector development.

In the second half of the last decade, Côte d’Ivoire showed significant political commitment to this issue by supporting the digitisation of part of its public services. The advent of a digital university for 3,500 students, is a symbol of the place that digital technology is taking in constructing the near future.

Abidjan continues its race to become the leading innovative ecosystem in French-speaking West Africa, with more than 20 innovation hubs. It includes Seedspace, a connected coworking hub present in emerging countries, as well as four Jokkolabs - coworking and support spaces for digital projects imported from Dakar.

The results are already observable in terms of the trickle-down of technology into Ivorian society. The Fondation Jeunesse Numérique, headed by telecommunications engineer Linda Nanan Vallée, plays an important role as an incubator of digital innovations in Côte d’Ivoire. It has enabled the incubation of more than 260 digital projects and supported some fifty start-ups.

Senegal

In Senegal, since 2017, the operator Orange has set up Orange Digital Ventures Africa (ODVA), a €50 million investment fund dedicated to economic and social innovation projects based on mobile applications. The Government has launched a 25-hectare Digital Technology Park (PTN) project in Diamniadio, on the outskirts of Dakar. A cornerstone of the national digital economy strategy “Senegal Digital 2025”, the technopole aims to support a genuine digital research economy in order to sustain the West African digital ecosystem. The Park will offer hosted companies a whole connected environment, including a data centre, an audiovisual production studio, as well as training and research institutions.

Governance and

cyber security

While Internet connectivity has generated new innovative services, capabilities and forms of sharing and cooperation, it has also generated new forms of crime, abuse, surveillance and social conflict.

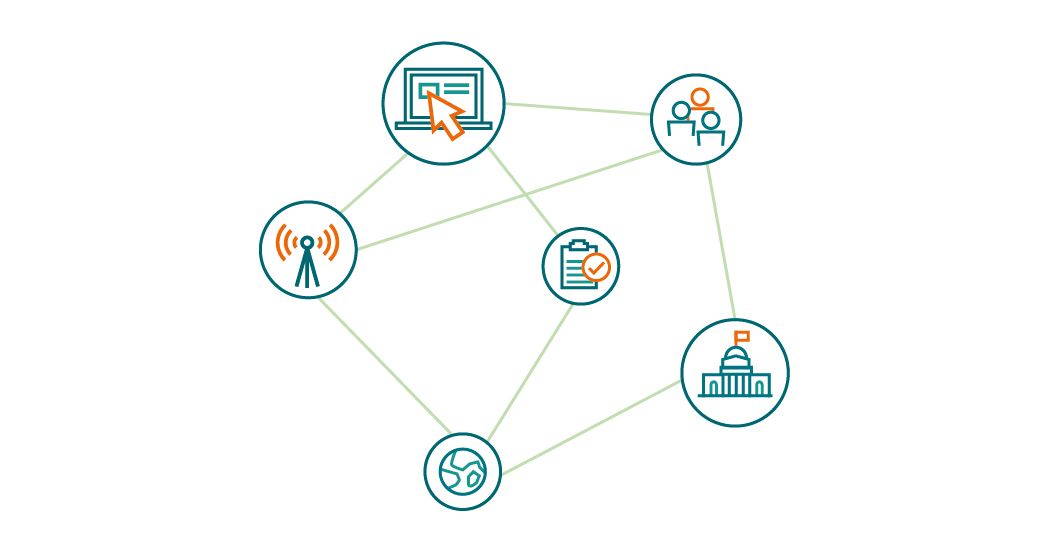

Internet governance implies a polycentric, less hierarchical order; it requires transnational cooperation between standards developers, network operators, online service providers, users, governments and international organisations.

It is difficult to see how sub-Saharan Africa can “go digital” unless governments develop and update their national digitisation strategies.

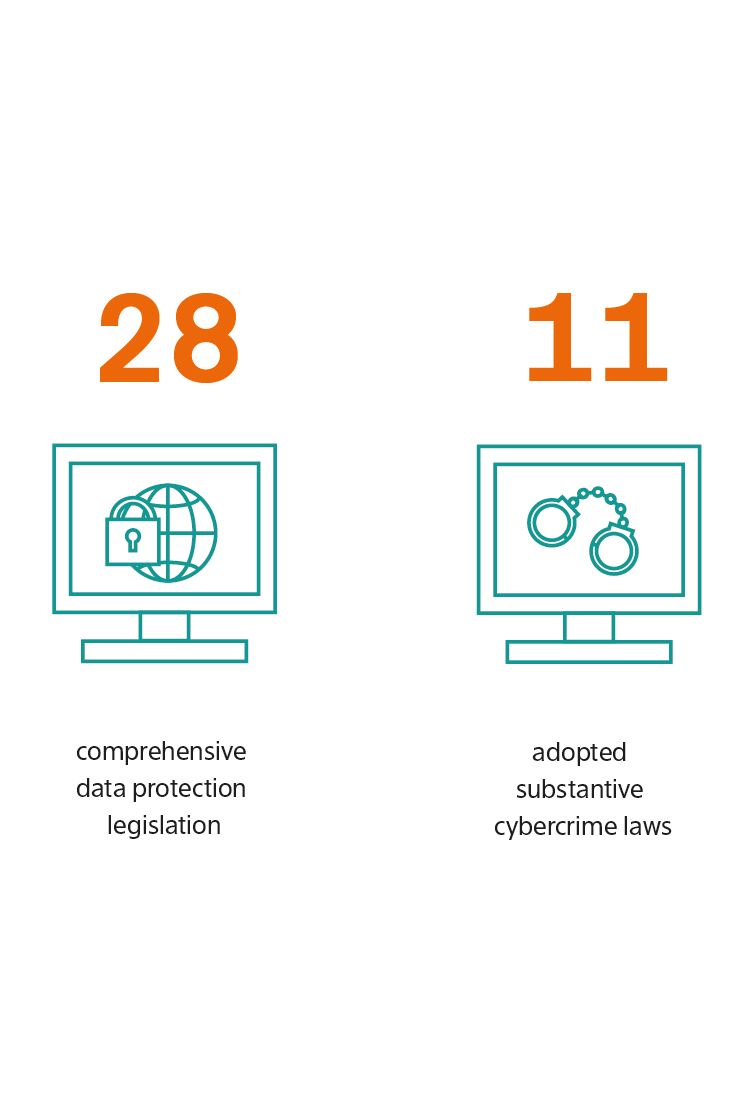

In 2021, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), only 28 African countries have comprehensive data protection legislation, while only 11 countries have adopted substantive cybercrime laws. The lack of digital strategies and legislation leads to serious security gaps that make countries vulnerable to the misuse of digital platforms and data.

At the same time, other challenges exist for Internet governance in Africa. Across the continent, a number of technology-related policies, such as imposed Internet blackouts or emerging tax regimes for social media, complicate the access to the market and to innovation for online users and technology entrepreneurs. Data protection and privacy has become a sensitive issue for Internet governance in Africa, in particular in a number of countries that have increased surveillance of online communications during election periods.

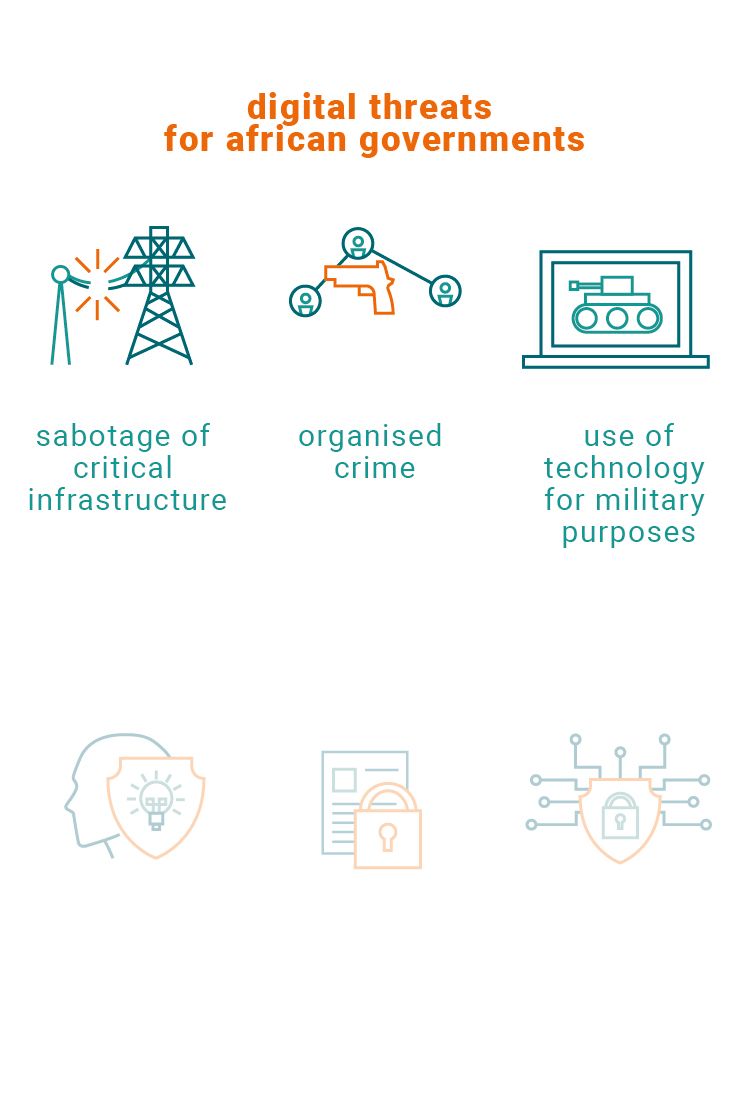

According to the Africa Centre for Strategic Studies (ACSS), African governments face a rapidly evolving set of digital threats – sabotage of critical infrastructure, organised crime and the use of technology for military purposes. For this reason, African governments should focus on three key issues – intellectual property (IP) protection, data protection and cyber security.

The Rwandan example?

“We are really close to seeing this dream come true. In Rwanda, for example, most of the government’s administrative services are now online, which has led to greater efficiency, a huge reduction in bureaucracy and the elimination of corruption.”

Jean Philbert Nsengimana, former Rwandan Minister of Information and Communications Technology (ICT), and Youth in 2016

Rwanda has become the spearhead of smart governance and is also the home of the Smart Africa initiative, which has two objectives: to make ICT a driver of the continent’s socio-economic development and to provide fast and reliable broadband Internet access to all. Rwanda wants to become an important centre of digitalisation in Africa and to this end is investing more in the development of the Rwandan university.

It is interesting to note that the topic of urban governance seen through the lens of technology, or ‘smart governance’, becomes a relevant topic for sustainable urban development. One of the pillars of digital governance aims to foster transparency by improving service delivery and promoting citizen engagement through ICT, simplifying citizens and businesses interaction with government and improving empirical decision-making in cities.

The states

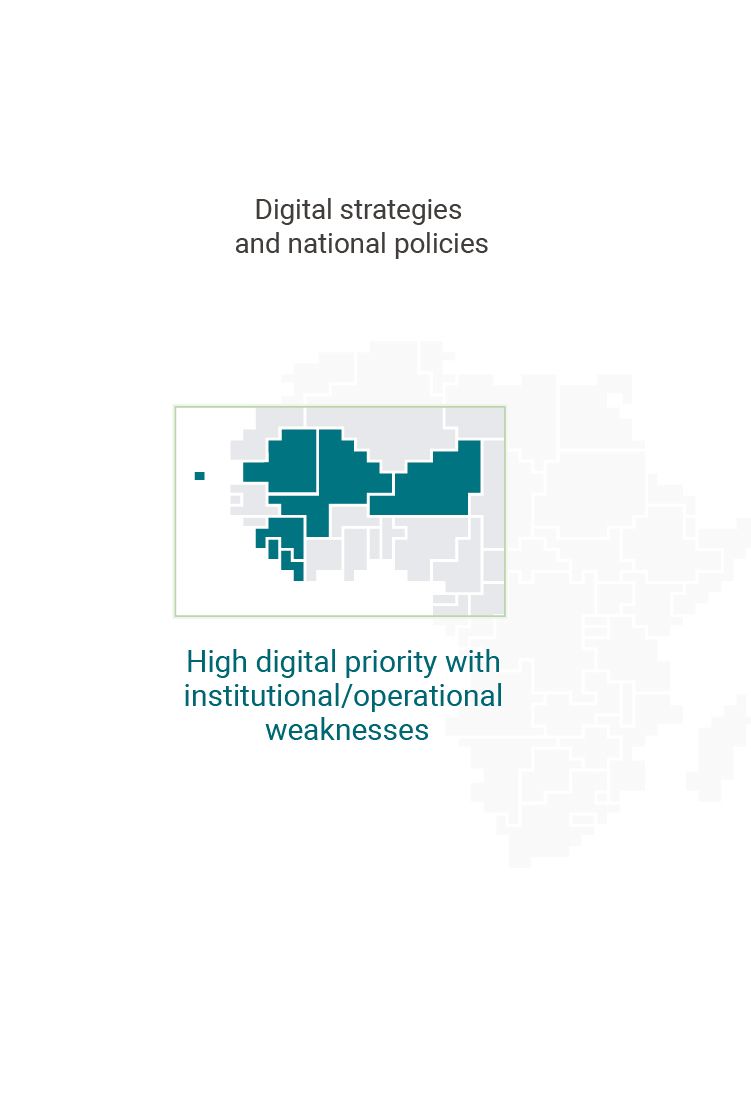

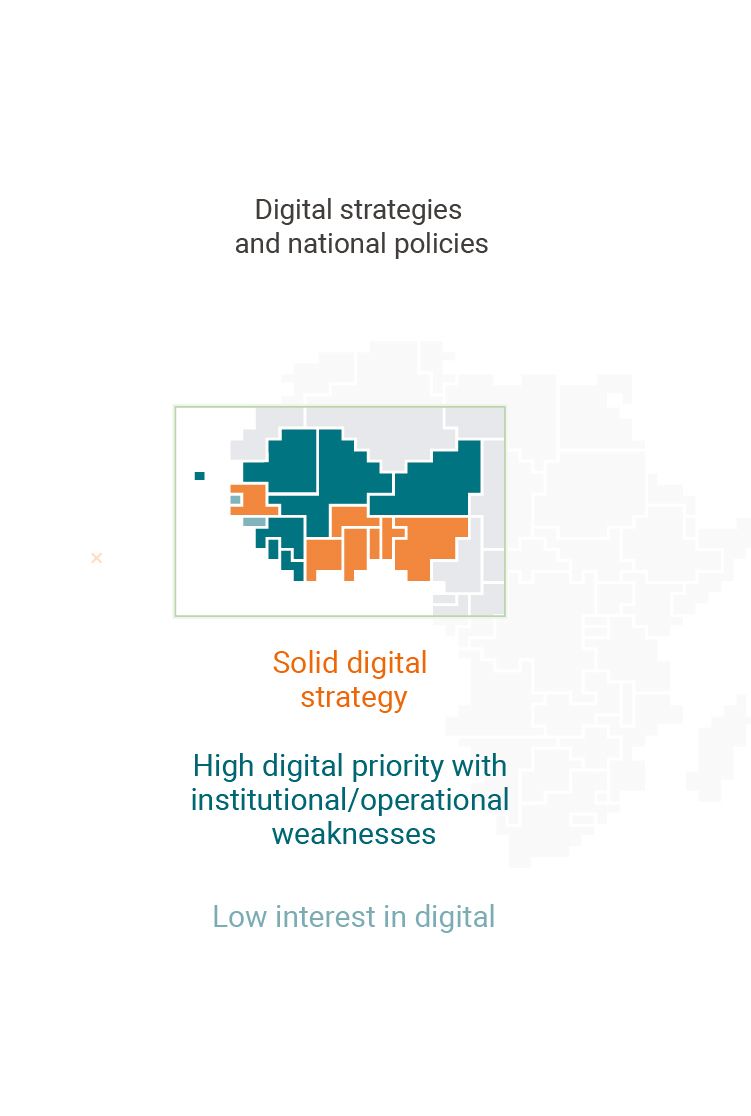

In West Africa, countries are now integrating digital strategies to their policies to define and address a broader spectrum of public problems.

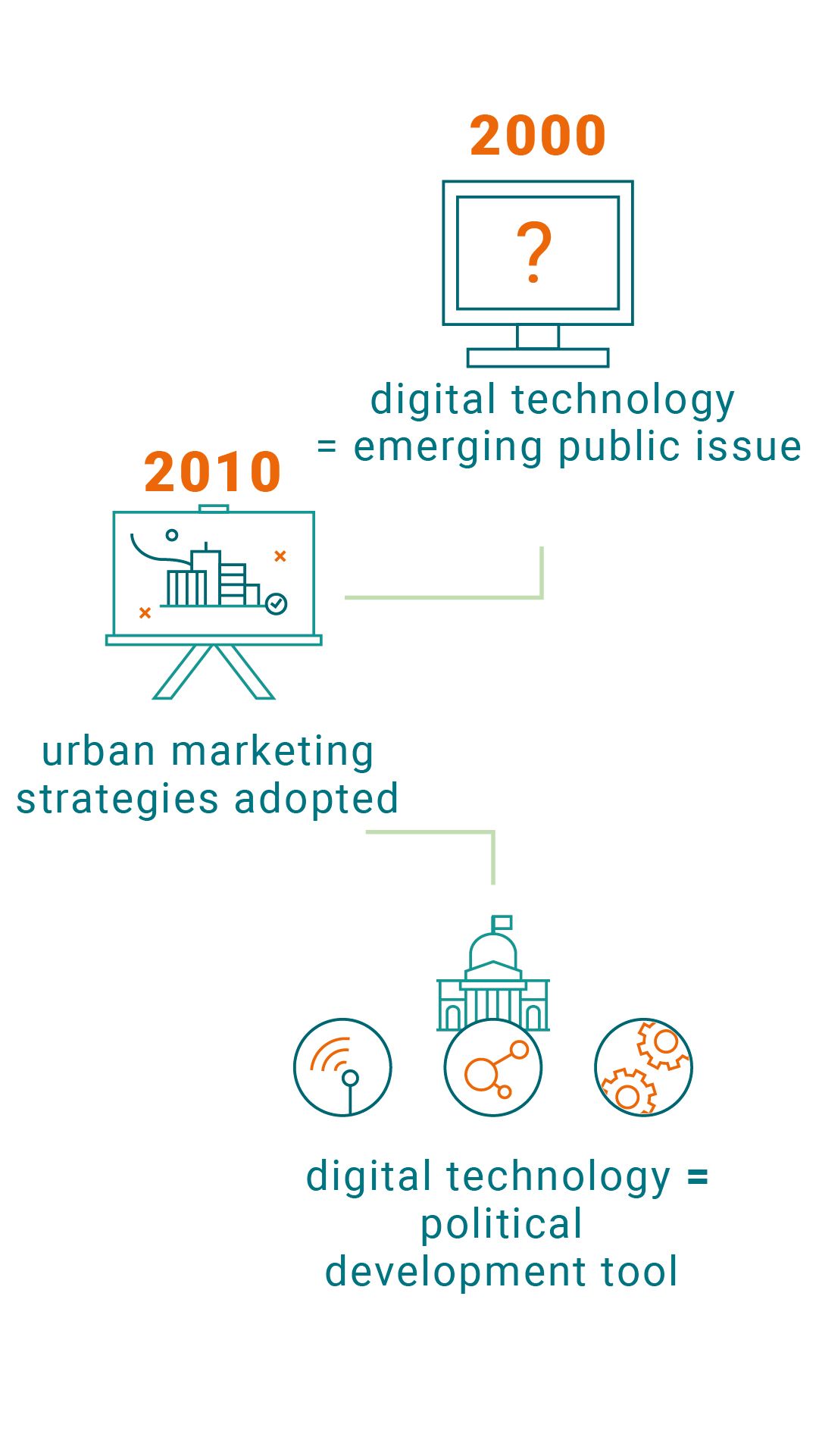

In the 2000s, digital technology appeared as an emerging public issue.

During the last decade, the largest African cities adopted urban marketing strategies centred on digital technology. This has supported the circulation in the public arena of digital development issues. If on the one hand, cities have become the preferred area of intervention for experimenting digital technology, on the other hand digital technology is now a tool for building public policies at national level. Digital technology is both a condition for cities renewal and a reference for a new digital and connected society.

Several countries are engaged in a process of digitalisation of society. The presence of institutions and sectoral policies focused on the translation of digital technology into a broad spectrum of fields of intervention in society. As in Benin, the continued improvement of Internet coverage and connectivity remains a priority, with a focus on broadband and high speed for business needs. We are witnessing second-generation digital policies that strengthen the capacity of actors to seize opportunities linked to digitalisation to transform society. The focus is rather on institutions and the consolidation of a legal framework for the development of e-governance. These countries stand out in promoting policies that use digital technology as a development tool that supports access to well-functioning essential public services, as well as a strategy to combat poverty.

However, some highly ambitious public policies lack a thorough assessment of the current context and the necessary resources to achieve a digitisation.

What role for universities?

The proximity of universities to the main actors of the digital world is now of public interest. These institutions have a major role to play in training engineers, entrepreneurs and technicians in the digital sector.

Digital training capacity in West Africa is crucial for the future of digitalisation in the region: it is about counteracting the brain drain dynamics that affect Africa’s high-tech sectors.

Both public and private actors are anticipating this reality by supporting the development of higher education as well as access to training equivalent to that provided in Europe. In Lagos, the proximity of Google Developers Spaces to the University of Lagos and one of the largest hubs in Africa, CC Hub, has supported the creation by Google of the Black Founders Fund Africa. This recognition of the potential of young graduates from West Africa by Google is also a recognition of the training offer in the sub-region, which has evolved considerably since the second half of the last decade.

© Dominic Chavez/World Bank

© Dominic Chavez/World Bank

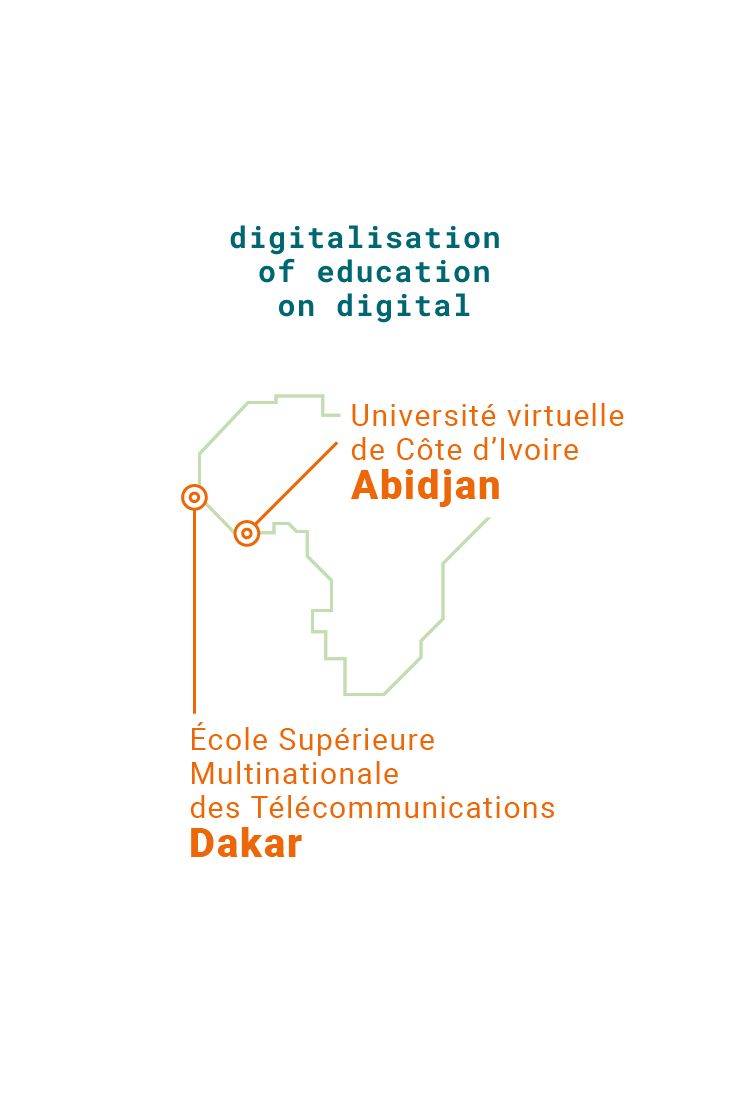

Most universities are now working on digitalising their training offer, making it possible to increase accessibility to higher education and training. Following the example of the École Supérieure Multinationale des Télécommunications in Dakar, higher education institutions are aware of the need for digital training and the challenges to overcome. In Abidjan, the Virtual University of Côte d’Ivoire has been training 6,000 students in computer science and digital science since 2016. This innovative training is linked to the creation of a doctoral school, which paves the way for research and development in digital technology in West Africa - a field previously reserved for start-ups and livings labs. The Ivorian Government has worked on the link between the university and the digital economy. Thus, the creation of the Fondation Jeunesse numérique supports the development of young entrepreneurs and strengthens start-ups in their innovation projects. Thus, helping to channel the potential of young graduates. Through the Virtual University of Côte d’Ivoire, the Government is, therefore, structuring the foundations of its digital ecosystem by investing in higher education and setting up relay institutions that channel high-level graduates wishing to launch into digital innovation.

© U.S. Embassy Ghana

© U.S. Embassy Ghana

Other West African countries have also adopted this model by developing digital universities for cutting-edge research fields, such as robotics, in Senegal and Burkina Faso. West Africa has thus distinguished itself by its ability to provide quality training in cutting-edge technologies and was selected by the World Bank to host the Pan African Robotics Competition (PARC) on four occasions. These events co-organised by universities do not only serve as a springboard for young entrepreneurs, they provide evidence to major players in the digital sector that West African youth have the capacity to create solutions for sustainable development.

The expectations for ICT and digital training in West Africa are so high, that a private market for digital training is emerging. The network operator Orange has launched “Orange Campus Africa” in partnership with the virtual universities of Senegal and Tunisia, as well as French schools. “Orange Campus Africa” is a teaching platform shared by these institutions. It aims to be accessible to students in West African countries that host the Orange telephone network.

The university is positioning itself as a key player in building the local skills needed for digital innovation in African cities.

A review of scientific literature shows that digital technology’s contribution to sustainable development can only be achieved if there is an ecosystem into which it can be effectively implemented. This is particularly true in cities, which face significant socio-environmental and economic challenges.

Nevertheless, cities still constitute the ideal environment for the implementation of effective digital technologies.

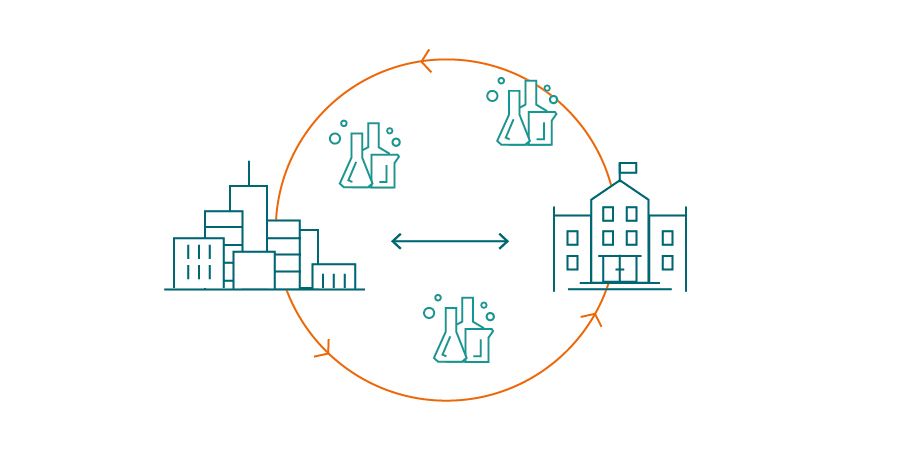

The analysis also reveals a lack of synergy between universities, local industries, multinational companies, civil societies and governments. It is becoming increasingly clear that for the “digital revolution” to take place, all actors - and in particular those in the public sector - need to collaborate closely.

The lack of technical and financial resources, the digital divide within cities, data protection and transparency of procedures are major challenges for all cities worldwide.

In essence, there is great potential in West Africa for unprecedented, collaborative and innovative cooperation.

The partnership model between university and city is ideal to implement these measures. The digital sector can benefit from academic skills and university research, which too often lack adequate means to test their innovations “in real life”. Meanwhile, cities will benefit from local academic expertise to find tailor-made solutions to their development issues.

Taking into account all relevant interests and the gap in investment capacity between the public and the private sectors, the international cooperation has an important role to play in ensuring that the digital revolution benefits all parties.

The analysis also reveals a lack of synergy between universities, local industries, multinational companies, civil societies and governments. It is becoming increasingly clear that for the “digital revolution” to take place, all actors - and in particular those in the public sector - need to collaborate closely.

Nevertheless, cities still constitute the ideal environment for the implementation of effective digital technologies.

The analysis also reveals a lack of synergy between universities, local industries, multinational companies, civil societies and governments. It is becoming increasingly clear that for the “digital revolution” to take place, all actors - and in particular those in the public sector - need to collaborate closely.

The lack of technical and financial resources, the digital divide within cities, data protection and transparency of procedures are major challenges for all cities worldwide.

In essence, there is great potential in West Africa for unprecedented, collaborative and innovative cooperation.

The partnership model between university and city is ideal to implement these measures. The digital sector can benefit from academic skills and university research, which too often lack adequate means to test their innovations “in real life”. Meanwhile, cities will benefit from local academic expertise to find tailor-made solutions to their development issues.

Taking into account all relevant interests and the gap in investment capacity between the public and the private sectors, the international cooperation has an important role to play in ensuring that the digital revolution benefits all parties.

The use of digital technology in the context of West African cities

under the direction of Jérôme Chenal

Chiara Ciriminna, Rémi Jaligot,

Karine Ginisty, Florian Rudaz